Dear reader,

I’m in the North End of Boston, sitting on the sofa of a friend who I’ve known since the third grade. I’ve been traveling for over 24 hours, and still have more to go before I make it to my mother who lives in a small town made of bricks on the eastern seaboard.

Tonight Andrea and I walked the waterfront, got loose at Trader Joes, ate cured meat and soft cheese, compared our relationships and skincare routines, and let The Office and Gilmore Girls play in the background while perusing a stack of cookbooks. This is what I need to do the night before I see my mother for the first time in almost two years.

I want to write about dementia, about the impulse to text my mother in all caps as if bigger letters will ensure she remembers what I’ve told her, like speaking louder to somebody who doesn’t understand your language in the first place. I will, but not tonight.

I’ll be away from the ranch, and from T., for the next three weeks. Tonight’s letter is about knowing when to keep promises to myself and when to let myself off the hook. It’s about water. It’s about the last time I was among redwoods.

The river looked magical in the sun, like a shiny, glistening pool of jade. A racket of children dragged an inflatable raft towards the water’s edge, while a sleepy couple made coffee in an Aeropress on a picnic table at their campsite. A young girl in a purple helmet and fleece pajamas skateboarded bum-first across the bridge; her father followed suit. T. and I walked a path along the riverbank, taking turns plunging in the water nearby the perfect resting spot of a fallen log.

We swim separately, I’ve noticed. Perhaps because it grants us the unparalleled sensation of a solitary dip during an otherwise shared ritual. It allows us to watch each other more fully, less distracted — of this I am sure.

T. always gets in first. In the beginning of our relationship, I stayed out of the water unless we were surfing in wetsuits. Fully clothed and perched on a piece of driftwood or a cliffside boulder, I’d watch as T. boldly submerged his body in whatever creek, river, or ocean swell we happened upon. I convinced myself that I didn’t mind staying behind.

Despite knowing the history of how water has saved my life (see: the last five years), I mostly held myself apart from its transformative powers for months after moving to the central coast. Sometimes it is hard to get in when it is cold. Sometimes it is hard to let go. Sometimes I don’t want to be healed.

It was only when T. emerged from a recent plunge in a seemingly born-again state, as if he had been completely rearranged, that I remembered what I was denying myself. I do mind opting out, and keeping my hair from getting wet has never served me.

From that day onward, I promised myself I would plunge everywhere that was plunge-able. And even though sometimes there is a snake floating on the surface, a stranger’s dog barking at me from the shore, or a sky full of clouds, I’ve kept to it.

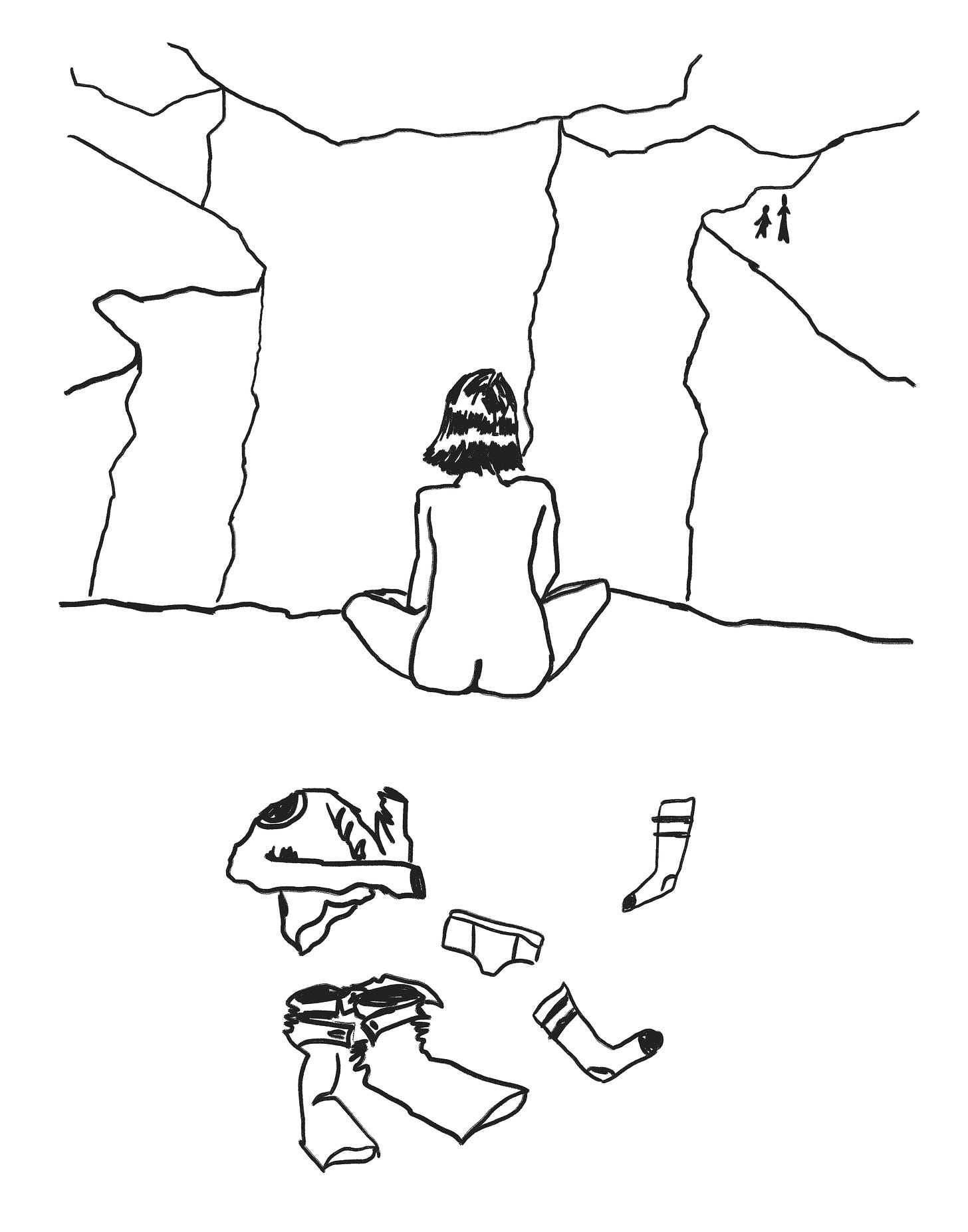

Sitting side by side, we air-dried in the sun together. Our wet curls mirrored one another’s. Water droplets streamed from the ends of our hair, rolling onto our collarbones and down our chests. I felt the sun dry my naked skin. I waved at the cars driving by up above.

We hiked to the gorge and ran into a group of our friends along the way. The river was rushing from recent rains, and high water levels had created a dicey obstacle course in order to reach an elusive swimming hole. In a swimsuit and Hokas, I did my best to climb, scramble, and wade my way through the divide, until eventually I sat myself down on a rock in the middle of the river for a stop and think.

The “stop and think” is one way I tend to myself in group settings or activities. Highly sensitive and easily influenced — not to mention one of nine roommates — I never regret making space for this practice, even if I end up lagging behind everybody or missing out on the cool thing entirely.

T. and our friends forged on. From my post, I watched for half an hour as everybody worked together through a clusterfuck of maneuvers to get to the other side. Eventually, I saw each friend make it to a clearing, and one by one, they leapt into the air and disappeared into an abyss, one that I may never see.

As the sole person left behind in a group of seven, I felt self-conscious. I wondered why I didn’t want to go with them. Was I scared? Did I not care about the swimming hole? Did I just need to be alone? Perhaps scrambling around the gorge half-naked had already provided me with enough expansion for the day.

I considered if my challenge was not to climb the rocks to the swimming hole, but to give myself the permission not to. I knew I’d savor the plunge once I’d made it over. I also knew getting through the gauntlet meant pushing myself to blend in and belong, for the sake of proving something to other people, and not for the experience itself.

I’m suspicious of pursuits behind which the approval of others is the motivating factor, and so I decided not to move ahead. I like this quality about myself, but I still anticipated a shame-spiral. Being kind to myself when I choose the opposite, more cautionary, or seemingly less fun version of what everyone else does has never been my default mode. More than once I asked T. if he thought I was being lame.

But then I surprised myself. Left to my own devices, I felt peace. I was okay with staying behind, and I was not an asshole to myself about it. I sat on the rock, felt my toes go numb, and ate a grapefruit while looking up at the sky through a clearing in the trees. Big Sur is beautiful. May it always be so.

A really lovely insightful and caring piece, which I could relate to both personally and for my neurodiverse children - I am a people pleaser and it's important I understand what is right for me, and to give my children the space to do what is right for them.

I too had a difficult relationship with a parent, my father, having caused complex PTSD during childhood, for which at times I truly hated him. Towards the end of his life he had many health problems including dementia brought on my chemotherapy. I always found it difficult to communicate with him and to manage my feelings, tho I grew to understand/empathise with him more and more as I got older (I'm 55) - I generally, but not always, found it not as hard as I'd envisaged to be with him, and was lucky to have seen him a couple of weeks before our first Covid Lockdown in the UK, when he died about a month later. I had to view the funeral online and found closure difficult. I take a great deal of comfort from that final visit when, although he couldn't form a sentence, we truly connected and new that we each loved each other.

I wish you all the best and hope this helps.

Thank you for sharing

Pete

A beautifully written story and one to which I can wholeheartedly relate. Thanks Anna. ❤️